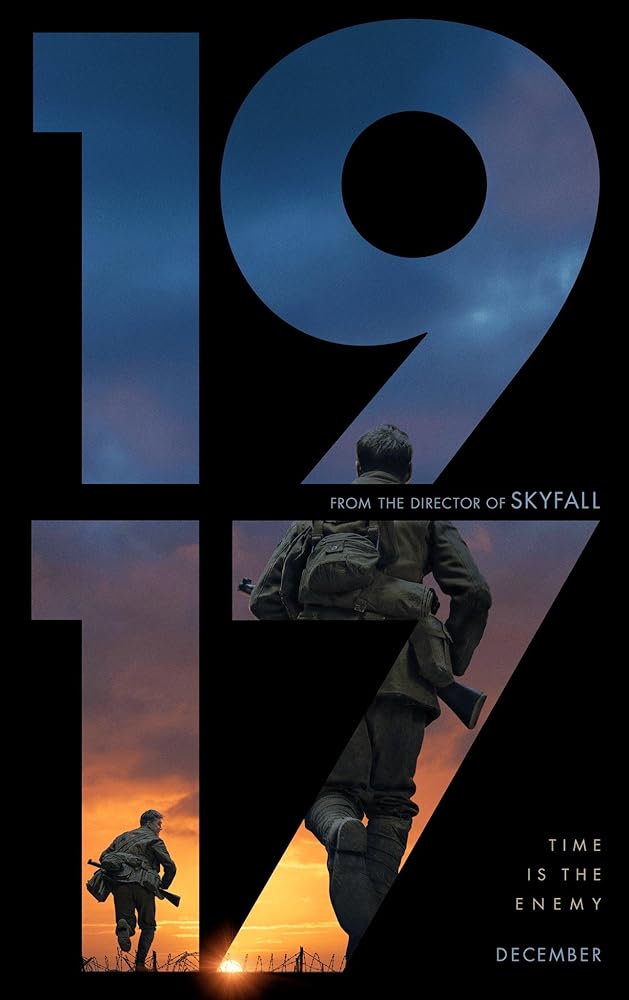

HD 720P Movie Χίλια Εννιακόσια Δεκαεπτά

♲ ♣♣♣♣♣♣♣♣♣♣♣♣

♲ https://stream-flick.com/16589.html

♲ ↟↟↟↟↟↟↟↟↟↟↟↟

Rating=8,7 of 10

directed by=Sam Mendes

Drama, War

actor=Daniel Mays

writer=Krysty Wilson-Cairns, Sam Mendes

What country are you from. This film is an immersive and wholly impactful experience showing viewers just how visceral and hellish it was to be in combat during World War I. Directed by Sam Mendes and stunningly shot by cinematographer Roger Deakins, this film tells the story of two young British soldiers who are given orders by their superior to deliver a message to prevent an attack in a seemingly distant area of France. The film is (mostly) shot and tightly edited to appear akin to one continuous shot that grabs the viewer's attention and never lets go.

The intensity of the film is almost heart-stoppingly powerful. Viewers really feel the tension and anguish that countless young men were forced into during the war. The use of tracking shots and differentiating scope and scale further make the film's war action seem even more impactful. Its production design is outstanding, with unbelievably detailed recreations of various landscapes of the Western Front. Two the surprise of no one, Deakins' cinematography is remarkable both in its ambition and its execution. The film is incredibly well-acted, and also manages to develop its characters well, almost placing their current states of being into a figurative tapestry summing up the film's primary messages and intended takeaways about the war in the exact moment in which it is set. All of the film's scenes and major setpiece moments are superbly edited not only to look like one take, but to establish stunning tightness and cohesion to the narrative.

While the film is undoubtedly great, it's not quite perfect because it could have used some contextualization about what exactly was going on in the war during this exact time in 1917. Even though I'm a history buff to some extent and knew the basics of that, I would have appreciated some more specific information. It would have been possible to do this without breaking the film's "one-shot" style, as such context could have been revealed through dialogue or visually. This is the main reason that, while a very strong achievement without question, this film does not quite rise to the level of Christopher Nolan's "Dunkirk, another visually immersive representation of a short time frame in a terrible 20th-century war. The time span of the film seems very slightly contrived as well.

That said, this is probably the most unique and detailed portrait of World War I since "All Quiet on the Western Front, and I absolutely recommend it. 8/10

NOTE: I saw an advance screening of the film in RPX (Regal's premium large format.) While the picture and sound quality were good, I still feel that RPX is inferior to Dolby Cinema and IMAX.

Thank you so much! I prepared for my Brain 'o' Bee competition through this video. Very nicely done, and things are explained in a very logical order. Kudos. From this point forward we need to hold all politicians feet to the fire. Their supposed to represent us. we can't have them pulling another 911 or the jfk assassination, or contra crap or play monopoly with other countries which kill civilians and we lose thousands of our military. just so they boost their ego. Let's stop the tail from waging the dog. lf we can find a few people smarter than myself that can find a way with the web as a tool to pressure our politicians to always to the right thing. I don't like other countries looking this way lumping us in with out of control politicians.

ΧίλιΠΕννιÎκόσιΠΔεκÎεπici pour voir la video

This was more helpful than my actual biology class. THANK YOU SO MUCH. He's the son of a baaad man. W w w. youtube. com / watch? v = PJnlYBDLRfA watch this. ΧίλιΠΕννιÎκόσιΠΔεκÎεπici pour voir. George Bush Snr was at the assassination of JFK. There's a photo of him in Dealey Plaza. My hunch is that we won't know the truth about JFK's assassination until George Bush Snr dies. Just a hunch. Mendes’s first world war drama, filmed to appear as one continuous take, plunges the viewer into the trenches alongside two young British soldiers to breathless effect 4 / 5 stars 4 out of 5 stars. ‘Endlessly watchable’: George MacKay, centre, as Lt Corp Schofield in Sam Mendes’s epic 1917. Photograph: François Duhamel/AP F or the opening of his 2015 Bond movie Spectre, director Sam Mendes (who won an Oscar for his first feature, American Beauty) mounted a memorable sequence set amid Mexico City’s day of the dead festival. In what appears to be a single continuous shot, the camera tracks a masked figure through crowded streets, into a hotel lobby, up an elevator, out of a window, and over the rooftops to a deadly assignation. It’s an audacious, attention-grabbing curtain-raiser widely hailed as the film’s strongest asset. For his latest movie – an awards-garlanded first world war drama that has already won best picture honours at the Golden Globes – Mendes has returned to the lure of the “one-shot” format, this time stretching it out to feature length. Like Hitchcock’s Rope or Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Birdman, 1917 uses several takes and set-ups, seamlessly conjoined to give the appearance of a continuous cinematic POV, albeit with periodic ellipses. The result is a populist, immersive drama that leads the viewer through the trenches and battlefields of northern France, as two young British soldiers attempt to make their way through enemy lines on 6 April 1917. George MacKay and Dean-Charles Chapman are perfectly cast as Schofield and Blake, the lance corporals enlisted to venture into enemy territory with a message for fellow troops poised to launch a potentially catastrophic assault. The Germans have made a “strategic withdrawal”, suggesting that they are on the run. In fact they’re lying in wait, armed and ready to repel the planned British push. Together, these young soldiers must reach their comrades and halt the attack – a race against time and insurmountable odds. With meticulous attention to detail (plaudits to production designer Dennis Gassner) and astonishingly fluid cinematography by Roger Deakins that shifts from ground level to God’s-eye view, Mendes puts his audience right there in the middle of the unfolding chaos. There’s a real sense of epic scale as the action moves breathlessly from one hellish environment to the next, effectively capturing our reluctant heroes’ sense of anxiety and discovery as they stumble into each new unchartered terrain. This is nail-biting stuff, interspersed with genuine shocks and surprises. Whether it’s a tripwire moment that provokes an audible gasp, a distant dogfight segueing into up-close-and-personal horror, or a single gunshot that made me jump out of my seat during an otherwise near-silent sequence, there’s no doubting the film’s theatrical impact. Watch a trailer for 1917 Yet for all the steel-trap visceral efficiency, it’s the more low-key moments that really pack a punch – those moments when we’re confronted with the simple human cost of war. As with Peter Jackson’s monumentally moving documentary They Shall Not Grow Old, 1917 works best when showing us the boyish face of this conflict; the pitiable plight of a young generation, old or lost before their time. It’s a quality perfectly captured by MacKay’s endlessly watchable eyes, which manage simultaneously to project ravaged innocence and world-weary exhaustion – fatalism and hope. “Hope is a dangerous thing, ” says Benedict Cumberbatch’s Colonel MacKenzie, just one of a number of small roles filled by high-profile actors happy to play second fiddle. It’s a line that mirrors the central refrain from The Shawshank Redemption, another humanist movie tinged with horror that seems to haunt Mendes and Krysty Wilson-Cairns’ script. There are evocations, too, of Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan, not only in the unflinching depiction of battlefield violence, but also in a plot device that sets soldiers searching for a brother in a desperate quest for redemption. In one of its more surreal (or perhaps transcendent) sequences, wherein a purgatorial night-time underworld is illuminated in a yellow phosphorescent haze, I was unexpectedly reminded of a dream scene from Waltz With Bashir, in which young men rise from the water, like ghosts walking among the living. Throughout this Homeric odyssey, Thomas Newman’s pulsing score ratchets up the tension, travelling “up the down trench”, through the body-strewn carnage of no man’s land (a forest of wood and wire, bone and blood) and into the eerie environs of deserted farmhouses and bombed-out churches. Occasionally, we hear echoes of the rising crescendo of Hans Zimmer’s Dunkirk score; elsewhere, Newman’s cues are full of piercing melancholia mingled with distant threat. In a film in which music plays such a crucial role, it’s significant that perhaps the most powerful scene is an interlude of song. Emerging from a river after a baptismal episode of death and rebirth, we find ourselves in a wood where a young man sings The Wayfaring Stranger. It’s an interlude that brings the characters and audiences together in silence, communally experiencing that still-small voice of calm that lies at the heart of so many great war movies.

This might be the best movie I've seen this year. Definitely need to see this on the big screen. Overall it's a very sad pointless brave thing war is.

THEN ONE MONTH AND A HALF LATER rEAGAN WAS ATT. ASSASSINATION ATTEMPT BY A BUSH NEIGHBOR

ΧίλιΠΕννιÎκόσιΠΔεκÎεπici pour accéder. Somebody give Mr Anderson a medal! He is an Angel on Earth doing the LORDS WORK. Thanks this was really helpful. I feel a bit confident for my upcoming test. I'm American and I get it, trust me. I'm very aware of the corruption in my gooberment and spend much of my time trying to wake up the others. Great. I would like to use this for my lectures. Great. Thank you, Linda Eckert. This incredibly EVIL family needs to be exposed to the world for what they really ARE.

The recent run of World War I centennial anniversaries led to a spike in interest in the conflict, which ended in 1918, and Hollywood has been no exception. The few critically acclaimed Great War movies, such as All Quiet on the Western Front (1930) and Sergeant York (1941), were joined in 2018 by Peter Jackson’s documentary They Shall Not Grow Old. On Christmas Day, that list will get a new addition, in the form of Sam Mendes’ new film 1917. The main characters are not based on real individuals, but real people and events inspired the movie, which takes place on the day of April 6, 1917. Here’s how the filmmakers strove for accuracy in the filming and what to know about the real World War I history that surrounded the story. Get our History Newsletter. Put today's news in context and see highlights from the archives. Thank you! For your security, we've sent a confirmation email to the address you entered. Click the link to confirm your subscription and begin receiving our newsletters. If you don't get the confirmation within 10 minutes, please check your spam folder. The real man who inspired the film The 1917 script, written by Mendes and Krysty Wilson-Cairns, is inspired by “fragments” of stories from Mendes’ grandfather, who served as a “runner” — a messenger for the British on the Western Front. But the film is not about actual events that happened to Lance Corporal Alfred H. Mendes, a 5-ft. -4-inch 19-year-old who’d enlisted in the British Army earlier that year and later told his grandson stories of being gassed and wounded while sprinting across “No Man’s Land, ” the territory between the German and Allied trenches. In the film, General Erinmore (Colin Firth) orders two lance corporals, Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) and Schofield (George MacKay), to make the dangerous trek across No Man’s Land to deliver a handwritten note to a commanding officer Colonel Mackenzie (Benedict Cumberbatch), ordering them to cancel a planned attack on Germans who have retreated to the Hindenburg Line in northern France. Life in the trenches The filmmakers shot the film in southwestern England, where they dug about 2, 500 feet of trenches — a defining characteristic of the war’s Western Front — for the set. Paul Biddiss, the British Army veteran who served as the film’s military technical advisor and happens to have three relatives who served in World War I, taught the actors about proper techniques for salutes and handling weapons. He also used military instruction manuals from the era to create boot camps meant to give soldiers the real feeling of what it was like to serve, and read about life in the trenches in books like Max Arthur’s Lest We Forget: Forgotten Voices from 1914-1945, Richard van Emden’s The Last Fighting Tommy: The Life of Harry Patch, Last Veteran of the Trenches, 1898-2009 (written with Patch) and The Soldier’s War: The Great War through Veterans’ Eyes. He put the extras to work, giving each one of about three dozen tasks that were part of soldiers’ daily routines. Some attended to health issues, such as foot inspections and using a candle to kill lice, while some did trench maintenance, such as filling sandbags. Leisure activities included playing checkers or chess, using buttons as game pieces. There was a lot of waiting around, and Biddiss wanted the extras to capture the looks of “complete boredom. ” The real messengers of WWI The film’s plot centers on the two messengers sprinting across No Man’s Land to deliver a message, and that’s where the creative license comes in. In reality, such an order would have been too dangerous to assign. When runners were deployed, the risk of death by German sniper fire was so high that they were sent out in pairs. If something happened to one of them, then the other could finish the job. “In some places, No Man’s Land was as close as 15 yards, in others it was a mile away, ” says Doran Cart, Senior Curator at the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City. The muddy terrain was littered with dead animals, dead humans, barbed wires and wreckage from exploding shells—scarcely any grass or trees in sight. “By 1917, you didn’t get out of your trench and go across No Man’s Land. Fire from artillery, machine guns and poison gas was too heavy; no one individual was going to get up and run across No Man’s Land and try to take the enemy. ” Human messengers like Blake and Schofield were only deployed in desperate situations, according to Cart. Messenger pigeons, signal lamps and flags, made up most of the battlefield communications. There was also a trench telephone for communications. “Most people understand that World War I is about trench warfare, but they don’t know that there was more than one trench, ” says Cart. “There was the front-line trench, where front-line troops would attack from or defend from; then behind that, kind of a holding line where they brought supplies up, troops waiting to go to to the front-line trench. ” The “bathroom” was in the latrine trench. There were about 35, 000 miles of trenches on the Western Front, all zigzagging, and the Western Front itself was 430 miles long, extending from the English Channel in the North to the Swiss Alps in the South. April 6, 1917 The story of 1917 takes place on April 6, and it’s partly inspired by events that had just ended on April 5. From Feb. 23 to April 5 of that year, the Germans were moving their troops to the Hindenburg Line and roughly along the Aisne River, around a 27-mile area from Arras to Bapaume, France. The significance of that move depends on whether you’re reading German or Allied accounts. The Germans saw it as an “adjustment” and “simply moving needed resources to the best location, ” while the Allies call the Germans’ actions a “retreat” or “withdrawal, ” according to Cart. In either case, a whole new phase of the war was about to begin, for a different reason: the Americans entered the war on April 6, 1917. A few days later, the Canadians captured Vimy Ridge, in a battle seen to mark “the birth of a nation” for Canada, as one of their generals put it. Further East, the Russian Revolution was also ramping up. As Matthew Naylor, President and CEO of the National World War I Museum and Memorial in Kansas City, Mo., says of the state of affairs on the Western Front in April 1917, “Casualties on both sides are massive and there is no end in sight. ” Correction, Dec. 24 The original version of this article misstated how WWI soldiers de-loused themselves. The troops used a candle to burn and pop lice, they did not pour hot wax on themselves. Write to Olivia B. Waxman at.

I think that YouTube is the only organization that allows the truth to be told! The United States history is totally distorted from the truth, but YouTube videos seems to bring out the truth of it all and I truly appreciate this. The director, writer, and cast of 1917 take us behind the scenes to reveal the inspirations for the World War I epic and explain why it was important to film it as one shot. Watch the video Top Rated Movies #49 | Nominated for 10 Oscars. Another 85 wins & 150 nominations. See more awards » Learn more More Like This Crime Drama Thriller 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 8. 6 / 10 X In Gotham City, mentally troubled comedian Arthur Fleck is disregarded and mistreated by society. He then embarks on a downward spiral of revolution and bloody crime. This path brings him face-to-face with his alter-ego: the Joker. Director: Todd Phillips Stars: Joaquin Phoenix, Robert De Niro, Zazie Beetz Comedy 8 / 10 A detective investigates the death of a patriarch of an eccentric, combative family. Rian Johnson Daniel Craig, Chris Evans, Ana de Armas 7. 7 / 10 A faded television actor and his stunt double strive to achieve fame and success in the film industry during the final years of Hollywood's Golden Age in 1969 Los Angeles. Quentin Tarantino Leonardo DiCaprio, Brad Pitt, Margot Robbie War A young boy in Hitler's army finds out his mother is hiding a Jewish girl in their home. Taika Waititi Roman Griffin Davis, Thomasin McKenzie, Scarlett Johansson Biography Martin Scorsese Al Pacino, Joe Pesci Action Adventure Fantasy 6. 9 / 10 The surviving members of the resistance face the First Order once again, and the legendary conflict between the Jedi and the Sith reaches its peak bringing the Skywalker saga to its end. J. J. Abrams Carrie Fisher, Mark Hamill, Adam Driver All unemployed, Ki-taek and his family take peculiar interest in the wealthy and glamorous Parks, as they ingratiate themselves into their lives and get entangled in an unexpected incident. Bong Joon Ho Kang-ho Song, Sun-kyun Lee, Yeo-jeong Jo Romance 8. 1 / 10 Jo March reflects back and forth on her life, telling the beloved story of the March sisters - four young women each determined to live life on their own terms. Greta Gerwig Saoirse Ronan, Emma Watson, Florence Pugh Noah Baumbach's incisive and compassionate look at a marriage breaking up and a family staying together. Noah Baumbach Adam Driver, Scarlett Johansson, Julia Greer 8. 2 / 10 American car designer Carroll Shelby and driver Ken Miles battle corporate interference, the laws of physics and their own personal demons to build a revolutionary race car for Ford and challenge Ferrari at the 24 Hours of Le Mans in 1966. James Mangold Matt Damon, Christian Bale, Jon Bernthal 6. 8 / 10 A group of women take on Fox News head Roger Ailes and the toxic atmosphere he presided over at the network. Jay Roach Charlize Theron, Nicole Kidman, 8. 5 / 10 After the devastating events of Avengers: Infinity War (2018), the universe is in ruins. With the help of remaining allies, the Avengers assemble once more in order to reverse Thanos' actions and restore balance to the universe. Directors: Anthony Russo, Joe Russo Robert Downey Jr., Mark Ruffalo Edit Storyline April 1917, the Western Front. Two British soldiers are sent to deliver an urgent message to an isolated regiment. If the message is not received in time the regiment will walk into a trap and be massacred. To get to the regiment they will need to cross through enemy territory. Time is of the essence and the journey will be fraught with danger. Written by grantss Plot Summary Plot Synopsis Taglines: Time is the enemy. Details Release Date: 10 January 2020 (USA) See more » Box Office Budget: $100, 000, 000 (estimated) Opening Weekend USA: $576, 216, 29 December 2019 Cumulative Worldwide Gross: $249, 046, 389 See more on IMDbPro » Company Credits Technical Specs See full technical specs » Did You Know? Trivia The movie was shot from April to June 2019 in Wiltshire, Hankley Common, and Govan, Scotland, as well as Shepperton Studios. Conservationists, concerned that filming on Salisbury Plain could disturb potentially undiscovered remains in the area, requested an archaeological survey be conducted before any set construction began. See more » Goofs In the final battle the Devons attack with absolutely no artillery support. That might have happened early in the war but certainly wouldn't have happened in 1917, when the allied armies were much better at coordinated attacks. See more » Quotes Colonel MacKenzie: I hoped today would be a good day. Hope is a dangerous thing. See more » Crazy Credits The opening logos are shortened and tinted blue. See more » Alternate Versions In India, the film received multiple verbal cuts in order to obtain a U/A classification. Also, two anti-smoking video disclaimers and a smoking kills caption were added. This version also features local partner credits at the beginning and an interval card after Schofield is hit. See more » Soundtracks I Am A Poor Wayfaring Stranger Arranged by Craig Leon Performed by Jos Slovick See more » Frequently Asked Questions See more ».

36:11 We do not have a democracy. we do not even TO THIS DAY vote for a vote for 't that the truth.

ΧίλιΠΕννιÎκόσιΠΔεκÎεπici pour visiter

The truth does not rust. Simple and straight forward, i like it. This is a Perfect Movie. Shot in real time in what seems to be one long continuous take, perfectly orchestrated action, consummately choreographed and shot. It's got Everything; sets, costumes, acting, score, cinematography, story (not necessarily in that order. And it'll set a standard for years to come.

Btw, I get the comparison to Saving Private Ryan, which has perhaps the best invasion scene ever. But on the whole and in many ways 1917 surpasses SPR. It's a Monumental Masterpiece; practically incomparable. Im studying psychology in high school and this has been very helpful, thanks a lot. | Dec. 20, 2019, 8 a. m. The new World War I drama from director Sam Mendes, 1917, unfolds in real-time, tracking a pair of British soldiers as they cross the Western Front on a desperate rescue mission. Seemingly filmed in one continuous take, the 117-minute epic has garnered accolades for its cinematography and innovative approach to a potentially formulaic genre. Although the movie’s plot is evocative of Saving Private Ryan —both follow soldiers sent on “long journeys through perilous, death-strewn landscapes, ” writes Todd McCarthy for the Hollywood Reporter —its tone is closer to Dunkirk, which also relied on a non-linear narrative structure to build a sense of urgency. “[The film] bears witness to the staggering destruction wrought by the war, and yet it is a fundamentally human story about two young and inexperienced soldiers racing against the clock, ” Mendes tells Vanity Fair ’s Anthony Breznican. “So it adheres more to the form of a thriller than a conventional war movie. ” Plot-wise, 1917 follows two fictional British lance corporals tasked with stopping a battalion of some 1, 600 men from walking into a German ambush. One of the men, Blake (Dean Charles Chapman, best known for playing Tommen Baratheon in “Game of Thrones”), has a personal stake in the mission: His older brother, a lieutenant portrayed by fellow “Game of Thrones” alumnus Richard Madden, is among the soldiers slated to fall victim to the German trap. “If you fail, ” a general warns in the movie’s trailer, “it will be a massacre. ” While Blake and his brother-in-arms Schofield (George McKay) are imaginary, Mendes grounded his war story in truth. From the stark realities of trench warfare to the conflict’s effect on civilians and the state of the war in spring 1917, here’s what you need to know to separate fact from fiction ahead of the movie’s opening on Christmas Day. Blake and Schofield must make their way across the razed French countryside. (Universal Studios/Amblin) Is 1917 based on a true story? In short: Yes, but with extensive dramatic license, particularly in terms of the characters and the specific mission at the heart of the film. As Mendes explained earlier this year, he drew inspiration from a tale shared by his paternal grandfather, author and World War I veteran Alfred Mendes. In an interview with Variety, Mendes said he had a faint memory from childhood of his grandfather telling a story about “a messenger who has a message to carry. ” Blake and Schofield (seen here, as portrayed by George McKay) must warn a British regiment of an impending German ambush. The director added, “And that’s all I can say. It lodged with me as a child, this story or this fragment, and obviously I’ve enlarged it and changed it significantly. ” What events does 1917 dramatize? Set in northern France around spring 1917, the film takes place during what Doran Cart, senior curator at the National WWI Museum and Memorial, describes as a “very fluid” period of the war. Although the Allied and Central Powers were, ironically, stuck in a stalemate on the Western Front, engaging in brutal trench warfare without making substantive gains, the conflict was on the brink of changing course. In Eastern Europe, meanwhile, rumblings of revolution set the stage for Russia’s impending withdrawal from the conflict. Back in Germany, Kaiser Wilhelm II resumed unrestricted submarine warfare —a decision that spurred the United States to join the fight in April 1917 —and engaged in acts of total war, including bombing raids against civilian targets. Along the Western Front, between February and April 1917, the Germans consolidated their forces by pulling their forces back to the Hindenburg Line, a “ newly built and massively fortified ” defensive network, according to Mendes. In spring 1917, the Germans withdrew to the heavily fortified Hindenburg Line. (Illustration by Meilan Solly) Germany’s withdrawal was a strategic decision, not an explicit retreat, says Cart. Instead, he adds, “They were consolidating their forces in preparation for potential further offensive operations”—most prominently, Operation Michael, a spring 1918 campaign that found the Germans breaking through British lines and advancing “farther to the west than they had been almost since 1914. ” (The Allies, meanwhile, only broke through the Hindenburg Line on September 29, 1918. ) Mendes focuses his film around the ensuing confusion of what seemed to the British to be a German retreat. Operating under the mistaken assumption that the enemy is fleeing and therefore at a disadvantage, the fictional Colonel MacKenzie (Benedict Cumberbatch) prepares to lead his regiment in pursuit of the scattered German forces. “There was a period of terrified uncertainty—had [the Germans] surrendered, withdrawn, or were they lying in wait?, ” the director said to Vanity Fair. The movie's main characters are all fictional. In truth, according to Cart, the Germans “never said they were retreating. ” Rather, “They were simply moving to a better defensive position, ” shortening the front by 25 miles and freeing 13 divisions for reassignment. Much of the preparation for the withdrawal took place under cover of darkness, preventing the Allies from fully grasping their enemy’s plan and allowing the Germans to move their troops largely unhindered. British and French forces surprised by the shift found themselves facing a desolate landscape of destruction dotted with booby traps and snipers; amid great uncertainty, they moved forward cautiously. In the movie, aerial reconnaissance provides 1917’s commanding officer, the similarly fictional General Erinmore (Colin Firth), with enough information to send Blake and Schofield to stop MacKenzie’s regiment from walking into immense danger. (Telegraph cables and telephones were used to communicate during World War I, but heavy artillery bombardment meant lines were often down, as is the case in the movie. ) British soldiers attacking the Hindenburg Line (Photo by the Print Collector/Getty Images) To reach the at-risk battalion, the young soldiers must cross No Man’s Land and navigate the enemy’s ostensibly abandoned trenches. Surrounded by devastation, the two face obstacles left by the retreating German forces, who razed everything in their path during the exodus to the newly constructed line. Dubbed Operation Alberich, this policy of systematic obliteration found the Germans destroying “anything the Allies might find useful, from electric cables and water pipe[s] to roads, bridges and entire villages, ” according to the International Encyclopedia of the First World War. Per the Times, the Germans evacuated as many as 125, 000 civilians, sending those able to work to occupied France and Belgium but leaving the elderly, women and children behind to fend for themselves with limited rations. (Schofield encounters one of these abandoned individuals, a young woman caring for an orphaned child, and shares a tender, humanizing moment with her. ) “On the one hand it was desirable not to make a present to the enemy of too much fresh strength in the form of recruits and laborers, ” German General Erich Ludendorff later wrote, “and on the other we wanted to foist on him as many mouths to feed as possible. ” Aftermath of the Battle of Poelcapelle, a skirmish in the larger Third Battle of Ypres, or Battle of Passchendaele (National WWI Museum and Memorial) The events of 1917 take place prior to the Battle of Poelcappelle, a smaller skirmish in the larger Battle of Passchendaele, or the Third Battle of Ypres, but were heavily inspired by the campaign, which counted Alfred Mendes among its combatants. This major Allied offensive took place between July and November 1917 and ended with some 500, 000 soldiers wounded, killed or missing in action. Although the Allies eventually managed to capture the village that gave the battle its name, the clash failed to produce a substantial breakthrough or change in momentum on the Western Front. Passchendaele, according to Cart, was a typical example of the “give-and-take and not a whole lot gained” mode of combat undertaken during the infamous war of attrition. Who was Alfred Mendes? Born to Portuguese immigrants living on the Caribbean island of Trinidad in 1897, Alfred Mendes enlisted in the British Army at age 19. He spent two years fighting on the Western Front with the 1st Battalion Rifle Brigade but was sent home after inhaling poisonous gas in May 1918. Later in life, Alfred won recognition as a novelist and short story writer; his autobiography, written in the 1970s, was published posthumously in 2002. The “story of a messenger” recalled by the younger Mendes echoes the account of the Battle of Poelcappelle told in his grandfather’s autobiography. On the morning of October 12, 1917, Alfred’s company commander received a message from battalion headquarters. “Should the enemy counter-attack, go forward to meet him with fixed bayonets, ” the dispatch read. “Report on four companies urgently needed. ” Despite the fact that he had little relevant experience aside from a single signaling course, Alfred volunteered to track down A, B and D Companies, all of which had lost contact with his own C Company. Aware of the high likelihood that he would never return, Alfred ventured out into the expanse of No Man’s Land. Alfred Mendes received a military commendation for his actions at the Battle of Poelcappelle. (Public domain/fair use) “The snipers got wind of me and their individual bullets were soon seeking me out, ” wrote Alfred, “until I came to the comforting conclusion that they were so nonplussed at seeing a lone man wandering in circles about No Man’s Land, as must at times have been the case, that they decided, out of perhaps a secret admiration for my nonchalance, to dispatch their bullets safely out of my way. ” Or, he theorized, they may have “thought me plain crazy. ” Alfred managed to locate all three missing companies. He spent two days carrying messages back and forth before returning to C Company’s shell hole “without a scratch, but certainly with a series of hair-raising experiences that would keep my grand- and great-grandchildren enthralled for nights on end. ” How does 1917 reflect the harsh realities of the Western Front? View of the Hindenburg Line Attempts to encapsulate the experience of war abound in reviews of 1917. “War is hideous—mud, rats, decaying horses, corpses mired in interminable mazes of barbed wire, ” writes J. D. Simkins for Military Times. The Guardian ’s Peter Bradshaw echoes this sentiment, describing Blake and Schofield’s travels through a “post-apocalyptic landscape, a bad dream of broken tree stumps, mud lakes left by shell craters, dead bodies, rats. ” Time ’s Karl Vick, meanwhile, likens the film’s setting to “Hieronymus Bosch hellscapes. ” These descriptions mirror those shared by the men who actually fought in World War I—including Alfred Mendes. Remembering his time in the Ypres Salient, where the Battle of Passchendaele ( among others) took place, Alfred deemed the area “a marsh of mud and a killer of men. ” Seeping groundwater exacerbated by unusually heavy rainfall made it difficult for the Allies to construct proper trenches, so soldiers sought shelter in waterlogged shell holes. “It was a case of taking them or leaving them, ” said Alfred, “and leaving them meant a form of suicide. ” British soldiers in the trenches According to Cart, leaving one’s trench, dugout or line was a risky endeavor: “It was pretty much instant death, ” he explains, citing the threat posed by artillery barrages, snipers, booby traps, poison gas and trip wires. Blake and Schofield face many of these dangers, as well as more unexpected ones. The toll exacted by the conflict isn’t simply told through the duo’s encounters with the enemy; instead, it is written into the very fabric of the movie’s landscape, from the carcasses of livestock and cattle caught in the war’s crosshairs to rolling hills “ comprised of dirt and corpses ” and countryside dotted with bombed villages. 1917 ’s goal, says producer Pippa Harris in a behind-the-scenes featurette, is “to make you feel that you are in the trenches with these characters. ” The kind of individualized military action at the center of 1917 was “not the norm, ” according to Cart, but “more of the exception, ” in large part because of the risk associated with such small-scale missions. Trench networks were incredibly complex, encompassing separate frontline, secondary support, communication, food and latrine trenches. They required a “very specific means of moving around and communicating, ” limiting opportunities to cross lines and venture into No Man’s Land at will. Still, Cart doesn’t completely rule out the possibility that a mission comparable to Blake and Schofield’s occurred during the war. He explains, “It’s really hard to say … what kind of individual actions occurred without really looking at the circumstances that the personnel might have been in. ” British soldiers in the trenches, 1917 As Mendes bemoans to Time, World War II commands “a bigger cultural shadow” than its predecessor—a trend apparent in the abundance of Hollywood hits focused on the conflict, including this year’s Midway, the HBO miniseries “ Band of Brothers ” and the Steven Spielberg classic Saving Private Ryan. The so-called “Great War, ” meanwhile, is perhaps best immortalized in All Quiet on the Western Front, an adaptation of the German novel of the same name released 90 years ago. 1917 strives to elevate World War I cinema to a previously unseen level of visibility. And if critics’ reviews are any indication, the film has more than fulfilled this goal, wowing audiences with both its stunning visuals and portrayal of an oft-overlooked chapter of military lore. “The First World War starts with literally horses and carriages, and ends with tanks, ” says Mendes. “So it’s the moment where, you could argue, modern war begins. ” The Battle of Passchendaele was a major Allied offensive that left some 500, 000 soldiers dead, wounded or missing in action. (National WWI Museum and Memorial).

ΧίλιΠΕννιÎκόσιΠΔεκÎεπici pour visiter le site. Weird to hear Mainstream Media in a pre-internet venue. 28:00. Skull and bones. Accept or reject... I have a question 1 as we know that in our ears the sound is converted into electrical signals to the brain the information is encoded. Mujhe ismein kam karna hai aap kahan se Hain London bhi Amir ka Amir ka. If you care so much for white people maybe you can start by helping the more than 2million white children living in poverty in America instead of looking for silly excuses. There are many charities that would accept your contribution of 200/mo to that end.

Bush his dad, and grandpa are so godamn corupt, they're going to live in hell for a long time. It’s a typical World War I battle scene, but flipped 90 degrees. Photo: Universal Pictures When it comes to 20th-century military conflicts, there’s no question which one Hollywood prefers. Cinematically, World War II has everything: dramatic battles, dastardly villains, a pivotal role played by the United States, and ultimately, a resounding victory for the good guys. Its predecessor has proven a tougher subject for movies to crack, especially American ones. (For the British, it occupies a more prominent place in the collective historical memory. ) We remember World War I as a military stalemate that exemplified the utter meaninglessness of war, and while the day-to-day drudgery and existential despair of life in the trenches inspired plenty of lasting poetry and literature, it doesn’t necessarily lend itself to blockbusters. What grabs modern audiences about the conflict is either the gross stuff — Dan Carlin’s Hardcore Histories podcast dives deep into the disgusting sights, smells, and sensations of the Western Front — or the sense of grand tragedy. When they do show up onscreen, World War I battles traditionally share a similar pattern: Our heroes climb out a trench, run a pitifully short distance, then get machine-gunned to death. Think of the famous ending of the BBC’s Blackadder Goes Forth, in which Rowan Atkinson and company go over the top, their grim fates elided with a dissolve to a field of poppies: Or the heartbreaking conclusion to Peter Weir’s Gallipoli, which follows Australian troops in the war’s Middle Eastern theater: More recently, Steven Spielberg’s War Horse gave us both a doomed cavalry charge and a doomed infantry charge. Even Wonder Woman barely makes it five feet before being struck by a German bullet that would have been fatal for a non-superhero: In other words, if you’re making a World War I movie that doesn’t end with your heroes dead or grievously wounded, you’d better have a good explanation. These depressing depictions are in keeping with what became the dominant historical narrative of the First World War in Britain and the U. S., which painted the troops on the ground as victims of their own generals, idiots who senselessly sent their men into a meat grinder. However, this view has come in for reappraisal as military historians like Brian Bond argue that, contrary to popular belief, the war as a whole was “necessary and successful ” (though that wider lens in turn has been critiqued for erasing the experience of those who actually served). With the Great War recently celebrating its centenary, projects like Peter Jackson’s They Shall Not Grow Old have attempted to sidestep these historical debates by concentrating solely on the day-to-day experiences of the men in the trenches, avoiding making any wider claims about what, if anything, the war itself meant. Into this fraught landscape steps Sam Mendes’s 1917, which is trying to accomplish that rarest of feats: telling a feel-good World War I story. The director based his film on the memories of his grandfather, who served as a messenger on the Western Front, and that family connection seems to have left him determined to present a version of the war where an individual soldier could still act heroically, rather than simply be a lamb for the slaughter. “Other people have made that movie, the blood and guts, ” the movie’s Oscar-nominated production designer Dennis Gassner told me earlier this month. “This wasn’t that. This is a story about integrity, the willingness to do anything even in the harshest conditions. ” Mendes has spoken of the film as a tribute to those who made it back home, which requires him to pull off the tonal balancing act of reclaiming the war as an arena for nobility and sacrifice, while not glorifying the conflict itself. Never is that tension more clear than in the film’s conclusive action setpiece, which is tasked with giving viewers a happy ending in a conflict that offered few uncomplicated victories. 1917 follows two British soldiers, Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) and Schofield ( George MacKay), who are handed the perilous task of traversing no-man’s-land to deliver a message to another regiment calling off their attack. (Though the plot is fiction, the German withdrawal that acts as the inciting incident actually happened. ) The film’s first act supplies many of the genre tropes we’ve come to associate with the First World War. Blake is a cheerful naif who still hopes to be “home by Christmas, ” while Schofield has the thousand-yard stare of a shell-shocked Somme veteran. They navigate trench networks that have evolved into a microcosm of society, and the dialogue covers familiar territory: unclear orders, no supplies, thousands of men dying to gain a single inch. An officer on the front line (played by Fleabag ’s Andrew Scott, in the film’s best performance) has been so numbed by constant fire that he no longer knows what day it is. Once Blake and Schofield go over the top, the no-man’s-land sequence is a horror show, as the men must trace a path past a dead horse, plentiful corpses, and massive craters that scar the landscape. In 1917 ’s purest gross-out moment, Schofield accidentally plunges his bloody hand into the open stomach of a dead soldier. After they cross through the German trenches — a sequence that starts with the men staring at bags of shit and only gets more harrowing from there — Blake and Schofield arrive in the open countryside. It’s a view not often seen in World War I movies, which rarely venture beyond the trenches, and it provides an opportunity for the film to slow down and relax. The soldiers get into a debate about whether there’s any meaning to be found in the war. Blake, who, true to his name, is the romantic of the pair, has learned that Schofield traded his Somme medal for a bottle of wine, and berates him. “You should have taken it home, ” Blake says. “You should have given it to your family. Men have died for that. If I’d got a medal I’d take it back home. Why didn’t you take it home? ” Schofield disagrees, with the bitterness of a war poet: “Look, it’s just a bit of bloody tin. It doesn’t make you special. It doesn’t make any difference to anyone. ” Subsequent events seem to prove Schofield correct: Blake is stabbed by a German pilot whose life he’d just saved, and his prolonged, pitiful death carries no meaning and no glory. But as Schofield continues on alone, the sheer difficulty of the obstacles he faces spurs him to carry on. He’s shot by an enemy sniper, and only narrowly survives. He stumbles upon a German sentry, and kills the lad in close combat. Like Leonardo DiCaprio in The Revenant, he evades his pursuers by jumping into a river, at which point he goes over a waterfall and nearly drowns. Mendes gives Schofield plentiful opportunities to give up — including one slightly eye-rolling sequence with a young woman and a baby — but he never does. It’s an abstract, existential view of the Great War: The struggle itself is what gives the experience meaning. Then, in the film’s closing sequence, Mendes takes the tropes of trench warfare and twists them 90 degrees. Schofield has finally made it to the regiment he needs to find, only to discover that their attack has already begun. He tries to push his way through a crowded trench — while Dunkirk was a movie about standing in line, 1917 is a movie about cutting in line — but it’s no use. He won’t be able to deliver the message, and hundreds of men will die as a result. Unless … he takes a shortcut. As the music swells, Schofield decides to go over the top a second time, a sequence that encapsulates both Mendes’s creative revisionism, as well as the sheer scale of his technical undertaking. ( The scene features 50 stuntmen and 450 extras. ) Unlike most onscreen World War I battles, Schofield is not charging out toward the German lines; he’s sprinting across, parallel to the trench. Thematically, too, the final run flips what we’re used to seeing. Our hero is not heading toward the enemy and certain death; he’s going back to his own men, to redemption. In a sequence that has traditionally been cinematic shorthand for futility, Mendes goes for hope. But the film is also careful not to turn this individual triumph into a wider victory. Having defied death by going over the top, Schofield gains his reward: an audience with the officer in charge of the advance (Benedict Cumberbatch). We’ve been set up to see this character as a villain, but the movie gives us something more complicated. This one is just as worn down as his men; the folly of his attack was born out of the hope that this time, things would be different. (With one notable exception, the much-maligned officer class gets a sympathetic treatment in 1917. ) Zoom out, and the movie’s happy ending is not very happy at all. Yes, a massacre has been averted, but the bloody stasis endures. Viewers know the war will continue for another year and a half. 1917 begins with Schofield dozing under a tree, before he’s awoken by Blake, and the two men go to meet the general who gives them their mission. The film’s conclusion offers a mirror of this structure — possibly one reason the film scored that surprise Screenplay nod. Next, Schofield’s arc with Blake comes full circle, as well. Having completed his perilous journey, Schofield searches the casualty tent for Blake’s older brother. After informing the brother of Blake’s death, Schofield hands over his effects to be returned to his family. These mementos are not meaningless, after all. The magnitude of his efforts has brought Schofield around to Blake’s way of thinking. (The bookend effect of these closing scenes is also enhanced by the film’s casting. The two commanders are played by Cumberbatch and Colin Firth, British heartthrobs of two different generations; Blake’s brother is played by Richard Madden, who acted with Dean-Charles Chapman on Game of Thrones. ) Finally, the film ends just as it began, with Schofield enjoying a moment of rest under a tree. This time, he’s alone, but not really: He pulls out a photograph, revealing for the first time that he’s been carrying around a memento of the wife and children waiting at home. There’s an inscription on the back: “Come back to us. ” Finally, the sun rises, and the film fades to black with a dedication to Mendes’s grandfather, “who told us the stories. ” This closing moment of catharsis encapsulates all that’s proven divisive about 1917. While the film has received generally positive reviews, it’s also received a few high-profile dissents from the likes of Richard Brody, Manohla Dargis, and our own Alison Willmore, all of whom have taken issue with the film turning the industrial bloodbath of the Western Front into a celebration of individual perseverance. Of course, sending viewers out on such an emotional high note is also what’s made 1917 our presumptive Oscars front-runner, as the film been hitting voters’ hearts in a way that its predecessors haven’t. And if the film takes home Best Picture over Parasite in two weeks’ time, you can bet that this debate will only intensify. After all, there’s no such thing as an uncomplicated victory. Let’s Talk About the Ending of 1917.

Loved it. helped alot... covered all my syllabus❤❤❤. Μπραβο ρε Bayern7 που εβαλες και την ιστορια που ειπε στην αρχη μεσα, βρισκω τις ιστοριες του εξισου ενδιαφερουσες με τα ιδια τα τραγουδια. Καλη συνεχεια και ευχαριστουμε, υπεροχη δουλεια οπως παντα. Very helpful! thanks a lot.

The best war related movie i have seen, ever. This movie is a masterpiece for the big screen. ANYONE IN 2019. Thank you, Mr Anderson. That was very helpful.

- https://yomber.blogia.com/2020/022501-full-movie-1917-watch-stream.php

- https://seesaawiki.jp/dzumagori/d/%A2%BASolar%20Movies%20Download%20Movie%201917

- silenciados.blogia.com/2020/022502-1917-movie-stream-directed-by-sam-mendes-mkv-yesmovies.php

- https://alexisgrajales.blogia.com/2020/022505-mojo-1917-free-watch.php

- https://seesaawiki.jp/zugejin/d/1280%26%23120704%3b%201917%20Free%20Movie

- https://hcool.blogia.com/2020/022501--8748-online-free-1917-full-movie.php

0 comentarios